| Host: | Alden Thompson |

|---|---|

| Guests: | Brant Berglin and John McVay |

| Quarter: | Ephesians |

| Lesson: | 1 |

| Sabbath: | July 1st, 2023 |

Study Guide Prepared by: John McVay

Key Texts: Acts 18-20; Eph 1:1, 2; 6:21-24

Key Questions

- Which of the events, listed below, provides the most help in understanding the setting of Ephesians? Why?

- One modern commentator writes, “‘Pound for pound’ Ephesians may be the most influential document ever written.”1Klyne Snodgrass, Ephesians, NIVAC (Zondervan, 1996), 37. Why do you think Ephesians has been so impactful?

- An Adventist author of yesteryear compared studying Ephesians to a mountain climber who “suddenly comes out at a place where bursts upon his vision a grand and enrapturing scene in every direction, filling his soul with wonder and admiration.”2Tyler E. Bowen, “From the Heights of Ephesians,” Review and Herald, August 21, 1919, 14. What passage or theme in Ephesians triggers a similar reaction from you?

- In what ways is the experience of the modern, Christian disciple similar to and different from the early Christian believers Paul addresses in Ephesians?

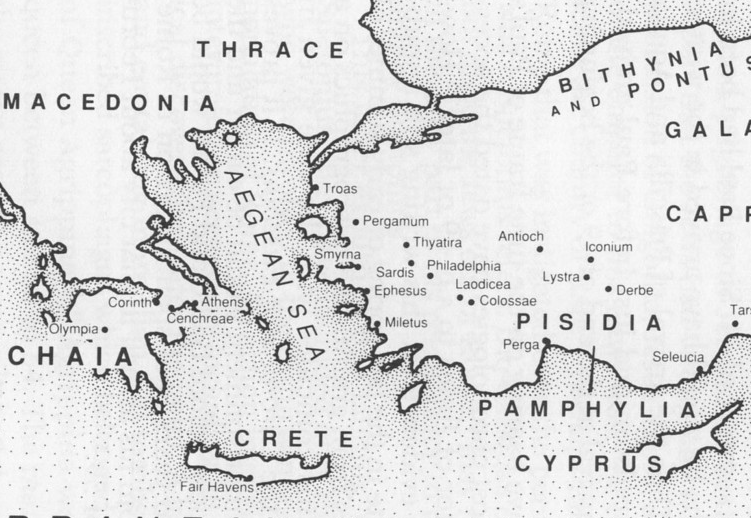

Why Ephesus? Paul does not randomly wander into the streets of Ephesus, the third or fourth largest city in the Roman Empire and the transportation center for the Roman province of Asia (see the map, below). He intends to found the Christian church there, traveling some 1,800 miles to arrive at the city: On his third journey, “Paul brought his years of experience together in the hub principle, establishing the Ephesus church as an equipping, multiplying hub of church-planting—to build movements elsewhere.”3Peter Roennfeldt, Following the Spirit: Disciple-Making, Church-Planting and Movement-Building Today (Warburton, Vic., Australia: Signs, 2018), 158. His strategy proved successful, with Ephesus succeeding Jerusalem as the powerhouse of Christian faith in the first century.

What prior events, recorded in Acts, provide the back story of Ephesians?

- Acts 18:18-21 – Paul’s initial visit to Ephesus (at the end of the second missionary journey, AD 52)

- Acts 18:24-28 – Apollos ministers in Ephesus (in Paul’s absence)

- Acts 19:1-20:1 – Paul ministers in Ephesus for 3 years (at the start of the third missionary journey, AD 53-56)

- Acts 19:1-10 – Paul’s baptizes twelve, speaks in the synagogue for three months, and teaches for two years in a lecture hall

- Acts 19:11-20 – The strange case of seven itinerant, Jewish exorcists, the sons of Sceva

- Acts 19:21-20:1 – The riot incited by the silversmith, Demetrius

- Acts 20:17-38 – Paul meets with the elders of the church of Ephesus at Miletus (at the end of the third missionary journey, AD 57; Note: Miletus is about 50 miles from Ephesus by modern roads; see the map, below)

How influential was the goddess Artemis and her cult in Ephesus? Ephesus was an important center for the imperial cult and for the practice of magic (cf. Acts 19:11–20) and dozens of deities were worshiped there. However, “Artemis of the Ephesians” (Acts 19:28; identified with the Roman “Diana”) dominated the politics, culture and economy of Ephesus and the city was the center of her widespread cult. Her richly decorated temple, the Artemision (Acts 19:23–41), was located outside the city walls. It was the largest temple in antiquity and was lauded as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world (see the portrayal of the temple, below). It served as the major banking center for the city and was the starting and ending point for bi-weekly, circuitous processions that featured images of Artemis. Coins displayed her image; regular, athletic games, the Artemisia, were conducted in honor of her. Her birth was celebrated elaborately each year, and a month of the year was named after her.

A huntress, Artemis was worshiped as “Queen of the Cosmos,” “heavenly God,” “Lord,” and “Savior” who controlled heaven, earth, the underworld, and the spirits who inhabited them. Statues show her in an elaborate costume, presenting various symbols of the power she offered to her worshipers. She wears the zodiac as a necklace or garland, symbolizing power over the supernatural and astrological powers that determined fate. She also wears a tight skirt featuring heads or busts of real and mythical animals, announcing her power over animals and demons.

What does Paul mean by his statement that “I fought with beasts at Ephesus” (1 Cor 15:32)? In 1 Corinthians, which Paul wrote from Ephesus, we find brief references to Paul’s time in the city. Paul’s introduction of Christian faith in Ephesus proved countercultural and disruptive, evoking both strong support and fervent opposition. Paul’s time there “was anything but an Aegean holiday”4Gordon Fee, 1 Corinthians, NICNT (Eerdmans, 1987), 769. featuring life-threatening conflict (2 Cor 1:8–10) against “many adversaries” (1 Cor 16:9) and “wild beasts” (1 Cor 15:32), probably best understood as a metaphorical reference to Paul’s combat against the evil spirits who inspired the sorcerers, idolaters, and the Artemis cult in Ephesus (cf. Acts 20:1 Pt 5:8; Eph 6:10-20).5See esp. Guy Williams, “An Apocalyptic and Magical Interpretation of Paul’s ‘Beast Fight’ in Ephesus (1 Corinthians 15:32),” Journal of Theological Studies 57 (2006): 42–56. Paul “is punning on Artemis’s identity as ‘mistress of wild beasts’ by likening her devotees to the animals she was known to protect.”6Daniel Frayer-Griggs, “The Beasts at Ephesus and the Cult of Artemis,” Harvard Theological Review 106, no. 4 (2013): 459–77. These events provide important context for Paul’s discussions in Ephesians of Christ’s power, expressed in the lives of the addressees (Ephesians 1:15–23; 2:1–10; 3:10, 14–21; 6:10–20; see Friday’s lesson).7See Clinton E. Arnold, Power and Magic: The Concept of Power in Ephesians (Baker, 1992).

What is the theme or theological message of Ephesians? Paul announces his theme early on (Eph 1:9-10) and works it out comprehensively in the letter. God has acted in Christ to initiate His plan “to unite all things in him [Christ], things in heaven and things on earth” (Eph 1:10 ESV) by creating the church as “one new humanity” (Eph 2:14) composed of both Jews and Gentiles (Eph 2:11-22; 3:1-21). Believers are called to act in concert with this divine plan (Eph 4:1-6:20), signaling to the evil powers that God’s ultimate purpose is underway (Eph 3:10).

Did Paul really write Ephesians? Paul introduces himself as author at beginning and end (Eph 1:1; 6:21-22) and often addresses the audience using the first person (Eph 1:15-16; 3:1; 4:1, 17; 6:18-20). Early and consistent attestation ensured that the epistle was readily accepted among the Pauline Epistles. Since the late 18th century, the authenticity of the letter has been questioned based on the vocabulary and style of the letter, the seemingly detached relationship it expresses between Paul and the addressees, the similarity with Colossians (with Ephesians viewed as a pseudepigraphical reworking of that letter), and the theology of the letter (which is seen as straying from Paul’s own views).

It is argued that Ephesians was a benign, “honest” fiction, with early Christians being fully aware it was not written by Paul. However, Ephesians does not fit the category since it offers no obvious indicators that it was falsified. Nor does it fit the category of deceptive pseudepigraphy, since such documents were crafted as weapons in the battle between orthodoxy and heresy and Ephesians is not a polemical document, but peaceful in tone. If pseudepigraphical, Ephesians urges the addressees to speak truth (Eph 4:14-15, 25-32; 5:9; 6:14) but lies about the author of the document without any motivation to do so.8I am summarizing here the arguments of Frank Thielman, Ephesians, BECNT (Baker, 2010), 1-5. Given the letter’s own claim, the early and consistent affirmation of the letter as coming from Paul, and the availability of reasonable explanations for the features of the letter mentioned above, it is best to affirm Ephesians as an authentic letter composed by Paul.

How does Ephesians end? Paul concludes with two brief, moving prayer benedictions (Eph 6:23, 24). The last two Greek words of the letter, en aphtharsia (“in incorruptibility” or “in immortality”) offer an interesting puzzle and are usually translated similar to the ESV, “Grace be with all who love our Lord Jesus Christ with love incorruptible.” Since the word “love” (agapē) does not occur in the final phrase and since such a translation fails to echo any central theme in the letter, there is opportunity to reconsider the suggestion that the phrase en aphtharsia be taken in a geographical sense, “in immortality,” and be seen as identifying the exalted location of “our Lord Jesus Christ”9See Ralph P. Martin, Ephesians, Colossians, and Philemon, Interpretation (Atlanta: John Knox, 1991), 79.: “Grace (be) with all who love our Lord Jesus Christ, (who dwells) in immortality” (cf. 1 Tim 1:17; Jas 2:1). In this view, the letter that begins with Christ “in the heavenly places” (Eph1:3) concludes with a benediction invoking grace for all who experience tender, deep, personal love for the resurrected, exalted, eternal Jesus (cf. Eph 1:19-23; 2:4-7).

Adapted from John McRay, Archaeology and the New Testament (Baker, 1991), p. 228

One Reconstruction of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus https://drivethruhistory.com/the-temple-of-artemis-at-ephesus/